NAME16

Kṣetrajñaḥ क्षेत्रज्ञः

Kṣetra is the gross body and Kṣetrajña is the soul. Chapter XIII of Bhagavad Gita is totally devoted to the discussion of Kṣetrajña and kṣetra. All these nāma-s distinguish the Brahman from other existences. This nāma endorses the essence conveyed through the previous nāma-s. This does not mean that ViṣṇuSahasranāma is propagating dvaita philosophy (dualism). The recitation of this Sahasranāma makes a person to advance in spirituality by enabling him to understand all the essential factors of spirituality in the beginning. By the time, a devotee recites the final nāma, he is ready for liberation. Hence, it is important to understand the meaning of each nāma.

Kṛṣṇa explains the difference between Kṣetrajña and kṣetra. “The body is termed as the field or kṣetra and the one who is knower of the field is Kṣetrajña. (In other words, matter is kṣetra and the soul functioning through it is Kṣetrajña.) Know Myself to be Kṣetrajña in all the Kṣetra-s.” Kṛṣṇa completes this chapter by saying, “Those who perceive with wisdom the difference between Kṣetrajña and kṣetra attain liberation.”

१६. || ॐ क्षेत्रज्ञाय नमः||

16. Om Kṣetrajñaay Namah

Kshetrajnah -One who knows the body and all the experiences from within the body, is the Knower-of-the- field, Kshetrajnah. As Brahmapurana would put it: Bodies are ‘fields’ and the Atman illumines them all without an effort, and therefore, is called Knower-of-the-field, Kshetrajnah”. One who knows, and can lead, the muktas to the exact place where the muktas will get their sought-after Supreme Bliss.

INTERPRETATION GUIDED BY SANT VANI (WORDS OF SAINTS)

Kṣetrajnaḥ

The knower of the world of objects. Kshetra is the objectified world. Jnah comes from the word Gyaan which means knowledge.

The Lord is the sākṣhī and also the kṣetrajnah, one who knows the kṣetra, the world of objects. The

Gitā enumerates briefly all that which is included in the kṣetra as the five subtle elements, ahankara, the Karta Bhaav–the sense of doership, buddhi–the cognitive faculty, avyakta–the unmanifest, the manifest, that is- the prakriti, the five organs of knowledge, the five organs of actions, the mind, the entire world of sense objects, the world of desires, aversions, sukha and duḥkha, the assemblage of this body, knowledge, fortitude along with all their modifications. (Bhagwat Gita 13.5.6). Thus the entire viśhva is called kṣetra. He is the one who resides in everyone as the subject, the knower.

You are the subject and everything else, including your body, mind and sense organs, is the object. Whatever is objectified is insentient and being insentient, it cannot objectify you, the subject. The stomach does not talk back to you as it is insentient, not conscious by itself! What is experienced are only sensations in the stomach. But we know for a fact that one’s stomach or for that matter, even the chair that one sits on, does not groan in pain verbally. Neither the stomach nor the chair are sentient, conscious. These cannot objectify me.

The initial stages of bhakti are based on the premise that the Lord is other than me. If the Lord is other than you, then He would also become an object of your consciousness. Like other objects in the world, the Lord, then, would be inert, dismissible and time-bound. If He is not an object, then is He the subject? If He were to be the subject, then, as a subject he would be subject to pleasure and pain, puṇya and pāpa as a result of his actions and therefore, become a saṁsāri, someone subject to a sense of limitations. But this is not so.

In fact He is both the subject and the object, both the kshetrajna and the kshetra. As kṣetrajna, he knows the entire kṣetra, which is pervaded by him. The kshetra is not any different from him.

In fact, the Lord is neither the subject nor the object – as both are limited. But, without Him, there is neither the subject nor the object.

Please watch upto 3.46min – knowledge of the Higher Self and merging with that Higher Self is the goal of all paths in spirituality.

“Sri Bhagavan Uvacha,

Idamshariramkaunteyaksetramityabhidhiyate,

Etadyovetti tam prahuhksetrajnahiti tad vidah”

“Arjun , you may consider, ME, as the Atman or Kshetragya of all the bodies in this world.

And according to me this knowledge of Kshetra or Kshetragya without any distortion is wisdom, in My views.”

Srimad Bhagavad Gita.

In Chapter 13 of Bhagwat Gita Arjuna asks for the clarification on six technical terms: prakṛti, Puruṣa, kṣetra, Kṣetrajña, jñānam and jñeyam. On scrutiny, even though six topics are mentioned by Arjuna, they can be reduced to 3 topics. The words kṣetrajñah, Puruṣah and jñeyam talk about the same principle: ātmā. The words kṣetram and Prakṛti are the same as anātmā. The sixth topic is jñāna which is separately discussed as the values that one must acquire to be able to attain self-knowledge. Thus, three topics essentially discussed are ātmā, anātmā and jñāna.

Verses 2 through 24

Any object of experience is anātmā; therefore, the entire universe is anātmā. Even the heavens come under anātmā. The very body itself is an object of experience because one is able to intimately experience the conditions of the body. Even the mind, including the intellect is an object of experience.

World + body + mind +their conditions = anātmā.

The nature of anātmā is described as follows:

– acetana-svarūpam – It is made up of matter and therefore inert. The sentiency of the body is not intrinsic, but borrowed. The mind is also made up of subtle matter.

– Saguṇam – endowed with varieties of attributes or properties

– Savikāram – subject to constant change or modifications.

Because of its changing nature, anātmā will go through two conditions:

– Manifest or visible condition – vyaktaavasthā

– Non-manifest or invisible – avyaktaavasthā – anātmā goes into this condition at the time of resolution

The manifest universe is prapañca and in the non-manifest state, it is called Maya.

The description of ātmā [Puruṣa, kṣetrajñah and jñeyam]:

The experienced object presupposes the presence of a subject, without whom the experience is not possible. The subject however is never available for objectification. The perception of the forms and colors presupposes the existence of the eyes, but the eyes themselves are not perceivable. Yet, there is no doubt that the eyes exist. Extending this principle, it can be concluded that the experienced objects prove the presence of a subject, but the latter can never be an object of experience. This experiencer principle is called ātmā. Ātmā is “I” the Consciousness principle that objectifies everything, but itself not available for objectification.

Ātmā is comparable to space (ākāśa) and light (prakāśa). The features:

– Ekam – Consciousness is one like space and light

– Acalam – everything moves in space but space itself does not move

– Akhaṇḍaḥ – space is indivisible. Ātmā is also indivisible

– Asaṅgaḥ – space is everywhere, but not contaminated by the objects within it.

– Sarva-ādhāram – space is the supporter of everything in it. Similarly, Consciousness is the supporter of matter (not vice versa). When one dies, the capacity of the body to express the Consciousness is lost. The Consciousness itself does not go away.

– Ātmā illumines everything like the light. Because of Consciousness everything is known including the darkness

This is ātma-anātma-viveka-jñānam. This is claiming that I am the Consciousness functioning through the body, but I myself am not the body. Medium arrives and departs, but I do not.

Jñāna

The word jñāna has a unique meaning this chapter: these are all the virtues (sadguṇa) required for gaining ātma-jñāna. A dharmic life with ethics and morality are pre-requisites for the Vedanta. Twenty values are enumerated without which one cannot understand the Vedanta. Even if someone understands it, it will only be academic knowledge.

Value + study = transformation

Study – value = (just) information

These values are presented in the śāstras as 4 D’s (sādhana-catuṣṭaya-saṃpattiḥ):

Discrimination – understanding that only Īśvara (Īśvaratattvam) can give permanent peace, security and happiness (pūrṇa) in life. The world cannot give this.

Dispassion – Once discrimination sets in, the priority changes in life. Īśvaratattvam becomes the primary priority and dispassion for the material world develops.

Desire – Dispassion leads to spiritual desire for pursuing the primary priority

Discipline – integrating the physical personality – body, mind and intellect act in unison. I become their master. This is required for disciplined study of the Vedānta.

These four values are expanded into 20 values in this chapter by Krishna.

Verses 25-35

Krishna concludes his teaching by presenting the stages that one must go through to attain this knowledge and its benefits.

There are five stages to attain this knowledge: karma yoga, upāsanā, śravaṇam, mananam and nididhyāsanam.

Karma yoga – perform actions to attain purity of mind.

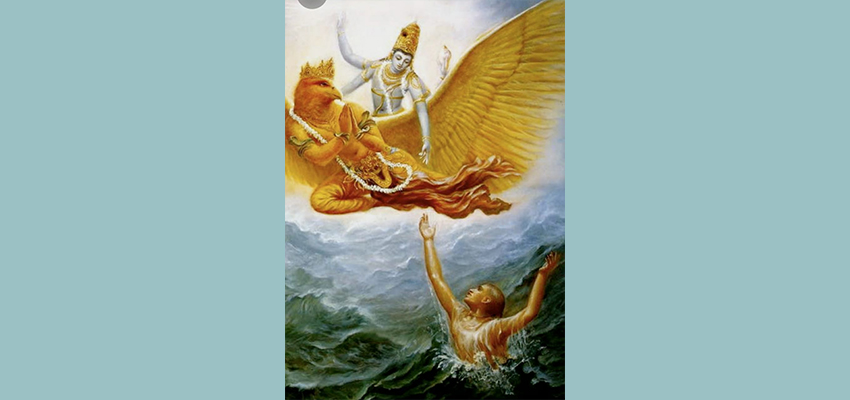

Upāsanā – meditation on Lord with attributes to remove the extroverted tendencies of the mind so that it becomes tranquil and focused

Śravaṇam – It is consistent and systematic study of Vedantic scriptures for a length of time under a competent Acharya.

Mananam – after comprehensive study, the doubts will be raised and removed

Nididhyāsanam – dwelling upon the teaching to change the perspective of the subject “I”. One’s predominant orientation is towards the body. This takes time to de-condition and change to the perspective that one is not the body, but the one functioning through the body.

At the end of these stages, one can claim: I am Brahman (aham brahma asmi).

The benefits of this knowledge:

Satvatra-samadarśanam – this person’s perspective has shifted from anātma to toātmā. Instead of seeing different waves, he now sees only the essence water. The practical benefit is freedom from attachments and aversions (rāga-dveṣa).

Amṛtattvaprāptiḥ – When I identified myself with anātmā, I was mortal, but when I now identify myself with ātmā, I am immortal.

Akartṛtvaabhoktṛtvaprāptiḥ – I am neither the doer (kartā) nor the enjoyer (bhoktā), but in my presence matter interacts with the world and undergoes changes

Brahmatvaprāptiḥ – I attain limitlessness. As a wave, I am limited, but as water, I realize that I am everywhere. This is jīvan-mukti.

Krishna concludes: Hey Arjuna, this knowledge will make a fundamental difference to you: this will take you from bondage to liberation. No other type of knowledge will give you this.

Questions received

In Gita, does kshetrajna means a jivatma or paramatma? Or sometimes they are interpreted

differently in different standpoints?

From the standpoint of the jivatma, kṣetrajna is the knower of the kṣetra-mind-body-sense complex. What is the status of this kṣetrajna? The Lord says I am the kṣetrajna in all the kṣetras. It is understood as a mahāvākya which is unfolded.

Can you explain in which context it is said that “the Lord is neither the subject nor theobject”?

Let ‘s look at the person, I assume the status of a subject, kartā (doer) when I do/ say things to people. When I am the subject, everything other than me is the object. When things – good, bad or ugly are done to me, I assume the status of object, bhogtā-the experiencer and the rest of the world assumes the status of a subject. It seems that my status of being subject and object are variable because I am not always the kartā nor am I always the bhogtā. I am the consciousness that gives reality to both the status of the kartā (doer) and bhogtā (experience).

The same is with the Lord – he is neither the kartā nor the bhogtā, neither the subject nor the object.